"By the lakeside there is an echo. As they stand there with an open book the chosen passages are re-uttered from the other side by a voice that be- comes distance and repeats itself . . . I say that that which is is. I say that that which is not also is. When she repeats the phrase several times the double, then triple, voice endlessly superimposes that which is and that which is not. The shadows brooding over the lake shift and begin to shiver because of the vibrations of the voice. —Monique Wittig, Lés Guérilleres

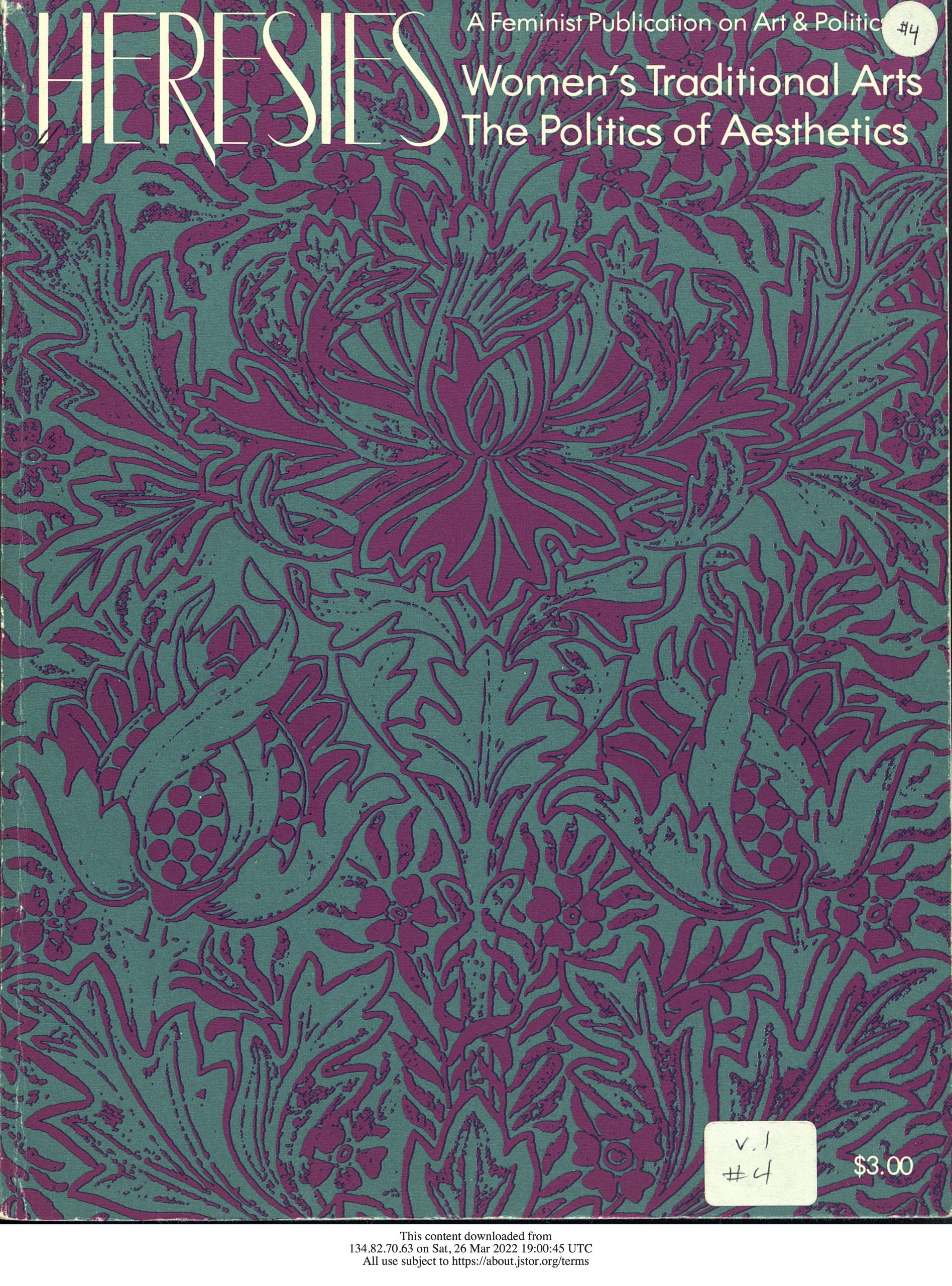

Delicate terra-cotta figurines were molded in clay by Agni women (Ivory Coast) as portraits destined for royal tombsFor a more complete history of women’s art we must know the actual circumstances of women’s creativity and aesthetic contributions to culture. Scholars of traditional societies* assume that men’s “art” is sacred and dangerous to women and children, while women’s “craft” is significant only in the daily sphere and of no prime importance. These assumptions obscure the real and complex situation of women’s artmaking and totally block an appreciation of their art.

We approached this article from different experiences. One of us, an anthropologist, is concerned with the current debates in feminist anthropological theory about women’s power or lack of it. One argument states that in all cultures women, no matter how actively they participate in the society’s life, are always considered inferior to men. Is this analysis true or are we so dependent on fragmentary reporting, usually based on the information of men, that we have not developed a way of knowing either women or their own evaluation of what they do? The other of us, a painter, interested for many years in the arts of Africa and the lives of African women, began this collaboration unknowingly influenced by the traditional arts of women. Both of us had been moved by the beauty of women’s art in traditional societies and wished to consider the ramifications of women’s public and private artmaking. This arti cle comes out of our readings and conversations.

By assembling and analyzing the sparse information on the art of women in traditional societies we hope to raise questions which will provoke further research. We have organized our discussion into categories which emphasize questions about the scope of women’s art and its relationship to their societies and to women’s status within those, societies.

THE ART OF WOMEN’S RITUALS

Birth, initiation, marriage and death are ritually celebrated by women in most societies and many female cults worship a patron goddess or god, but we can find only scattered references to the ritual art objects women make. Early missionary accounts of earth goddess rites in Nigeria’ state that ceramic votary objects and clay goddess figures were made by the priestesses and their female initiates. Recent reports do not mention women making these clay figures.? Agni women of Ghana and Mangbetu women of Zaire make ritual funerary ceramics with portrait heads. (This anthropomorphic art is considered atypical of women’s artmaking.) Ceramic “figurines,” abstract in form, are made by adult women in many African societies for the initiation rites of girls to explain the women’s view of women and sexuality. Made of sundried clay, these are rarely collected by museums and little known by scholars.? Is women’s ritual art not found because researchers assume that women do not make ritual art? We presume far more examples exist Extensive documentation of these objects is necessary to expand our knowledge of women’s art and their lives.

ART AS SYMBOLS OF AUTHORITY

Masks, free-standing figures and other carvings (appar- ently always made by men) are used as symbols of secular authority in traditional societies. Western anthropologists and collectors have been especially impressed by these forms, since they conform more closely to Western definitions of art. As the most frequently collected traditional artifacts, they are the most available for study These objects are believed to be invested with power anc the person who uses them wields that power. (Since they are usually commissioned, the artist is not identified with the object s power.) The literature implies that since women do not use these symbols of authority, they have little public power. The following examples show that these assumptions are not true.

In Sierra Leone and Liberia, the all-female Bundu society commissions masks for use as symbols of their authority. The helmet mask and woven body covering worn by the women lend an awesome appearance to their dance performance and are invested with such power that they are utilized both in funeral rites and in intimidating males or females who insult women. In the Ivory Coast *Tribal and peasant societies, with a nonmechanized technology, and with much social and political life centered on a kin group consisting of many generations connected by blood or marriage ties, not partaking indigenously of the Western cultural or economic tradition. 119 Page: 120 Woman dancer of the Bundu society wearing commissioned helmet mask. Woman from Hupa (north California) tribe in typical dress embellished with sea shells. Credit: Smithsonian Fulani woman (the western Sudan) wearing traditional hair style. 120 Senufo women commission carvings for use in their divination society, the Sandogo.“ Women’s divination is considered essential to determining outcomes of important events and discovering causes for social disruptions. Although male-commissioned Senufo masks have been well analyzed, the art of the Sandogo society is frequently not discussed, giving an unbalanced view of women’s power in this culture. In stratified societies, such as African cultures in which power was wielded jointly by female and male sovereigns, art work was commissioned by both, but we do not know in what ways it represented the female aspects of power.

Besides commissioned objects, women use dance to affirm their authority. Among the Kom and other groups in the Cameroons women participate in a disciplinary performance called anlu, if a parent or pregnant woman is insulted or beaten or an old woman abused, if incest occurs, or when the women of the village want to use discipline against men.

“Anlu is started off by a woman who doubles up in an awful position and gives out a high-pitched shrill, breaking it by beating on the lips with the four fingers. Any woman recognizing the sound does the same and leaves whatever she is doing and runs in the direction of the first sound. The crowd quickly swells and soon there is a wild dance to the tune of impromptu stanzas informing the people of what offence has been committed, spelling it out in such a manner as to raise emotions and to cause action . . Then the team leaves for the bush to return at the appointed time, donned in vines, with painted faces, to carry out the full ritual . . . Vulgar parts of the body are exhibited as the chant rises in weird depth ... [Account by Kom man].5

During the Aba riots of 1921 when 10,000 Ibo women demonstrated against the British, their final, most powerful show of force was a performance like anlu. In what other instances do women’s arts of authority exist and what forms do they take?

PERSONAL DECORATION

In many cultures personal ornamentation, perhaps more than any other art form, provides the basis for a complex system of signs. The body becomes a background on which messages about rank, wealth, sexual maturity, marital status and occupation are expressed. Clothing, jewelry, tattooing, scarification, body painting and hair styling are consciously designed to convey these messages. Young Zulu and Swazi women in southeastem Africa make necklaces as courting poems in which the beads are carefully ordered, each bead a metaphor for a range of meanings. White beads, for example, symbolize all that is good, and have cleansing and purifying powers. They appease ancestors, bring good luck and represent the heart and love itself.“ Because societies like these do not use writing, such codifications of messages are especially significant.

Excessive neck lengthening, knocking out of teeth, amputation of fingers, wearing of multiple weighty anklets, necklaces and bracelets, footbinding and clitoral and labial excisions are all done in the name of beauty Why is women’s personal decoration apparently more extreme than that of men of their cultures, and why do women s clothing and jewelry so often seem to hinder their Page: 121 Women’s wall murals in South Africa combine archaic and modern tech niques. This work portrays the village of the artist, a Ndebele woman Kulele Mohlangu. Credit: Thomas Matthews, African Arts mobility? To what extent is personal decoration an expression of self-identification and to what extent is it a sign of women’s being property and a reinforcement of women’s inferior status?

THE UTILITARIAN ARTS

Although frequently centered in the home, women’s utilitarian arts form a fundamental and pervasive part of the public visual aesthetic. Women create a visual enviror ment by the arrangement and cleanliness of their tents or compounds; the making of pots; the incising of calabashes; the weaving, dyeing and embroidering of cloth, baskets, mats and rugs; the application of quill and beadwork to cloth and skins; and the painting of murals and application of decorations to the interior and exterior walls of houses. In spite of the documentation of the existence of these arts, there is little analysis of them or of the status of the women who make them. Why has the impact of women’s art on their cultures been so neglected by scholars when it plays such a pervasive role in people’s lives?

Women’s traditional art has received little attention from Western writers not only because it is utilitarian but because it is almost always abstract. Neither the iconog- raphy, the formal structure nor the symbolism of women’s abstract images and patterns has received serious attention and analysis with a few exceptions, such as a study of bokolanfini, “mud” cloth made by Bamana women of Mali, which describes the designs as abstractions of specific historical events.” The assumption that women’s abstract designs have no meaning is directly related to the idea that traditional women artists are not creative. How do women’s choices of image and pattern reflect their traditions, their own inventiveness and concerns of their society?

In traditional societies men as well as women produce utilitarian art. Yet even when they work with the same materials their form, content and technique differ markedly (for example, Plain buffalo-skin robe designs and the loom widths in West Africa and Spanish America). There has been no satisfactory explanation of these differences. Western art scholars seem to favor psychobiological ex- planations, often ignoring the impact of historical events, such as colonialism and the introduction of foreign technologies.

Detail, Bokolanfini cloth. Resist-printed by painting negative areas with mud and decorated with motifs representing a nineteenth-century battle. The cross represents a Mauritanian woman’s cushion, which symbolizes no bility. Credit: Marli ShamirFEMALE MUSICIANS, BARDS AND SINGERS

Musical instruments are frequently particular to one sex or the other. Among the ! Kung of the Kalahari Desert men play hunting bows, with one end placed in their mouths. Adolescent girls play the pluriarch, the “women’s” instru- ment, which consists of several small bows attached to a box plucked by the fingers.” Adult women apparently are not musicians as often as men. In the context of dance !Kung women frequently provide the percussive back-up for men’s dances by hand clapping. For their own dances, melon tossing, women sing elaborate lyrics and provide their own hand clapping. Men can join the women’s dance although women cannot join that of men. How do musica instruments and musical performances by women reflect their roles and status in other spheres?

Through their lullabies women’s song universally pro- vides the earliest environment in which children develop language and musical sensibilities. When women work and perform rituals together and for each other, song and dance play an important part, but have rarely been record- ed. The songs’ explicit erotic content (often satiric and bantering) may have militated against fuller description.

Where women have major economic and social roles, as in tropical Africa, women s participation and leadership in public song and dance performance is traditional.? In other cultures where the sexual spheres are more clearly hierar chical, men s and women’s music is segregated. In rural Yugoslavia there are two categories of songs, “heroes’ songs and “women’s” songs. Sung before an audience by a single male, heroes’ songs idealize the male as heroic war- rior. All other songs are called women s songs and are usually sung in groups by women, children or men: by describing suffering and everyday reality, they reveal women’s skepticism and resistance to the heroic ideal.10

In many agrarian cultures when women sing alone before a public audience they are considered prostitutes. A respectable woman is therefore restricted in her public activities.1 Nomadic Arabic desert cultures, however, en- courage women poets of distinction to compose commen- taries on their society, which are sung in public. Among the Bagarra of the Sudan women bards sing the history of the group, lead warriors into battle with songs and in the system of tribal justice sing of the crime and punishment of the convicted. “In performance a (bard) always stands out in the position of respected authority, her wit is ap- preciated and her techniques for composition are copied by young women aspiring to her position of influence in the community.12 In what contexts are women’s musical per- formances a commentary on their culture’s history; and in what contexts do women articulate their own history, myths and opinions through dance and song!

Page: 122 Osage ribbon-work blanket. The hand motif may have represented family members, or perhaps it had a more mystical meaning.WOMEN ARTISTS’ COMMUNITIES

Traditional women artists work in groups either by col- laborating on one object (such as the long tapa cloths of Polynesia) or by establishing networks for techniques and innovations to be exchanged and for traditions to be taught. Women artists working as a community have been emphasized in research on Pueblo and African potters; Pomo, Yurok and Karok (California) basketweavers; and Plains quill and bead workers. Although expertise is recognized and acknowledged among these women, their artmaking is not highly competitive. In the village of Ushafa, Nigeria, women who “make the best ware only make special pots when commissioned to do so ... otherwise, their pots are made to be indistinguishable from the rest.”13 How do women artists interact and criticize each other’s work in traditional societies, and do their communities differ from those of men artists?

Since colonialism, commissions by traders who deal in traditional artifacts have tended to isolate experts from the other artists. Modern governments, by creating new training centers for the unskilled, have usurped the tradi tional roles of the experts. How does the alteration of their artistic communities affect women s art and status in their cultures?

Contemporary female bard of the Baggara of the southern Sudan Republic. Credit: R. C. CarlisleWOMEN’S ART AND CULTURAL CHANGE

With the introduction of new materials, the substitution of imported objects and the influence of new images. colonialism and cultural contact have altered the art of women in traditional societies. Women’s response has often been inventive, appropriating objects and images and putting them to novel use. In a Ghana village women decorate the exterior doorways of their houses with imported china plates, turned to expose the manufacturers inscriptions, which they consider picturesque.” Many colonized peoples, curious about other cultures, have incorporated their observations into their art, sometimes as ironic commentary, sometimes as an exploration of ’exotic” designs. North American Indian women devel- oped vine and flower patterns in their beadwork based, perhaps, on the crewel arts of the northern European colonists. The art of non-Western women has been appre- ciated in turn by Western women and used to decorate their homes. Near Eastern and native American rugs, for example, are a traditional women’s art which has had a special place in the aesthetic environment of Western people. In contrast to the intense interest of art historians in discovering exactly when Western artists first saw African masks, the influences of the women’s art from traditional societies on Western art of all kinds remains undocumented.

The impact of colonialism has been contradictory for women. In some cases it has weakened the hold of patriarchs over women. In others, by ignoring women’s traditional economic independence, it has provided education and employment primarily for men. If women are educated, they are required to sever connections with their own traditions. Most women, however, seem to retain the traditional fabrics and dress longer than men do, indicating, perhaps, both their skepticism about the benefits of modernization and their attempt to keep their cultural traditions intact. Modernization has sometimes eroded the barriers which traditionally prevented women from using anthropomorphic and zoomorphic images and from carving in wood and ivory.15 In addition, since colonialism, wider markets for both old and new forms of women’s art have developed.

Colonization and modernization have also had quite negative impacts on women’s artmaking. Institutions that once commissioned art produced by women, such as the refined tapa cloth used in Hawaii to wrap god-figures,16 have often disappeared as the result of contact with West- ern missionaries. The basis for sharing resources by women and men has also changed. Baule women thread- makers lost their traditional ownership of the cloth men wove from their thread when it was replaced by manufac- tured thread.1” Many of the utilitarian arts—local cloth. decorated hides, baskets and ceramics—have been replaced by imported cloth and plastic and metal containers. As traditional art forms are replaced by ones made from modern materials and by modern techniques, they may be- come rare commodities, sold to tourists and collectors.

Through such sales the entire history of women s art may disappear from the culture which produced it.

Although under modern influence women’s traditional arts may continue, usually new images, styles or techniques are developed. How have these changes occurred? What changes in quality and meaning take place when women artists use new materials and begin to produce art for unfamiliar buyers? With the expansion of Page: 126 Cuna women dancing. The molas which serve as panels on their blouses are sewn in appliqué and embroidery, using several layers of brightly colored cloth. This is the most complex visual art of the Cuna. Credit: F. Louis Hoover. the marketing of their arts has their economic base been eroded or strengthened? And, in those cases where the women’s traditional art has disappeared, how do women adapt to this loss?

We have reviewed some of the scattered evidence of the kinds of art women make in traditional societies and we have asked questions to stimulate further investigation. The few available in-depth studies were written mainly in the 1920s and 1930s by women anthropologists studying native American cultures.18 These ethnographers ap- proached their field research with the attitude that withir those cultures women’s participation was real, perhaps central, and as women they had greater access to informa- tion from women. Many of the questions we want answered now were not asked by them. In order to com- pile a more complete history of women’s artmaking, more ethnographies are needed, informed by feminist ideas. Women’s art from traditional societies excites us with its beauty and its relevance to life. We want to know more about the circumstances in which it is made, used and ap preciated. Only then will be begin to understand fully how women create culture.

We are at the lakeside. To construct a feminist history of women artists we must consider all that has been writ- ten and unearth more. We must consider all that has been left out, as well. We must talk with each other, and out of the dialogue will come new ideas, new critiques. Through the superimposition of what we have known and what we are insisting on knowing, we can dispel the shadows which have remained too long.

Karok basket, twined with knobbed lid, decorated with yellow porcupine quills and rich brown maidenhair fern stem. Credit: Denver Museum, YKa-58 lowa beaded moccasins (c. 1860) beaded in blue, green, red, pink, yellow and black. A fine example of a colorful abstract style which developed neai the Kansas-Nebraska border. (Private collection/American Indian Art)- 1. P. Amaury Talbot, Tribes of the Niger Delta (London: Sheldon Press, 1932), p. 94 and figures. In this and other works Talbot describes the roles of Nigerian women in the various cults of their tribes. These may include the making of figurines, symbol-laden pots, and wall decorations of shrines. It is unclear if women created figures for mbari houses, but they created portrait ceramics of ancestors and famous priestesses. Whether, and how, their religious art differed in form and function from that of men deserves further investigation.

- 2. See Herbert M. Cole, “Art as a Verb in Iboland, African Arts Autumn 1969, pp. 34-41; “Mbari is Life, Spring 1969, pp. 8-17; “Mbari is Dance, Summer 1969, pp. 42-51.

- 3. See Hans Cory, Ceramic Figurines: Their Ceremonial Use in Primi- tive Rites in Tanganyika (London: Faber and Faber, 1956).

- 4. Anita Glaze, “Power and Art in a Senufo Village, African Arts, Spring 1975, pp. 25-29, 64-67

- 5. Eyewitness account cited in Shirley Ardener, “Sexual Insult and Fe- male Militancy, in Perceiving Women (New York: Halsted Press, 1975), pp. 36-37

- 6. Regina Twala, “Beads as Regulating the Social Life of the Zulu and the Swazi, reprinted in Everyman His Way, ed. Alan Dundes (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1968), pp. 368-369

- 7. Pascal James Imperator and Marli Shamir, “Bokolanfini, Mud Cloth of the Bamana of Mali, African Arts, Summer 1970.

- 8. N. England, cited in Seth Reichlin, “Bitter Melons”: A Study Guide (Somerville, MA: Documentary Educational Resources, 1974), p. 27

- 9. Alan Lomax and Forrestine Paulay, Dance and Human History (film). Distributed by University of California Extension Media Center

- 10. Mary P. Coote, “Women’s Songs in Serbo-Croatian,” Journal of American Folklore, 90 (1977), pp. 331-33

- 11. Norma McLeod and Marcia Herndon, “The Bormliza: Maltese Folk song Style and Women, in Women and Folklore, ed. Claire Farrar (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1975), pp. 81-100.

- 12. Roxanne Connick Carlisle, “Women Singers in Darfur, Sudan Re- public, Anthropos 68, 1973, pp. 785-798.

- 13. Jane and Donald Bandler, “The Pottery of Ushafa, African Arts, Spring 1977, pp. 26-31.

- 14. Barbara Guggenheim, private communication.

- 15. Simon Kooijman, “Tapa Techniques and Tapa Patterns in Poly- nesia in Primitive Art and Society, ed. Anthony Forge (London: Ox- ford University Press, 1973), p. 110.

- 16. Mona Etienne, “Women and Men, Cloth and Colonization: The Transformation of Production-Distribution Relations among the Baule (Ivory Coast), Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines 65, XVII (1), 1977 (n.p.).

- 17. For example, Ruth Bunzel, The Pueblo Potter (New York: Dover Publications, reprint, 1969) and Lila M. O’Neale, “Yurok-Karok Basket Weavers, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 32, 1932, pp. 1-182.

Valerie Hollister is a painter of partial figures influenced by all kinds of decorative art. She lives in Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

Elizabeth Weatherford is a cultural anthropologist teaching at the School of Visual Arts in New York City. 123