Frida Kahlo (1910-1954) was one of those strong, vivid people who surmounts all sorts of odds. Unrestrained by her native Mex ico's male-dominant culture, Kahlo did pretty much what she pleased. Though she was best known as the wife of the renowned muralist, Diego Rivera, she was admired as a highly original painter whose work pursued totally different goals from her husband’s. While Rivera broadcast public messages on public walls, Frida Kahlo painted intensely personal images on small pieces of tin. At 15 Kahlo was crippled for life by a bus accident that almost killed her; yet she became famous for her heroic “allegría. She led a full and complex life, traveling to the United States and to France where she exhibited her paintings. Her house in the Mexico City suburb of Coyoacan, now the Frida Kahlo Museum, was a mecca for visiting dignitaries; the Riveras entertained everybody from Leon Trotsky to André Breton to Sergei Eisenstein.

But what perhaps most attracts the attention of people today is Kahlo’s painting. The majority of her paintings are self- portraits, the most accessible subject for someone who spent her life in and out of hospitals and did much of her painting in bed. Self-portraits were a way of confronting, confirming and extending her reality. Kahlo depicted precisely what was going on in her life—birth, abortion, miscarriage love, divorce, surgical operations, political passions, thoughts of death—with astonishing honesty. The result is a lasting record of female experience that strikes many resonances today. Indeed, Frida Kahlo has be- come something of a role model for women artists both in the United States and in Mexico.

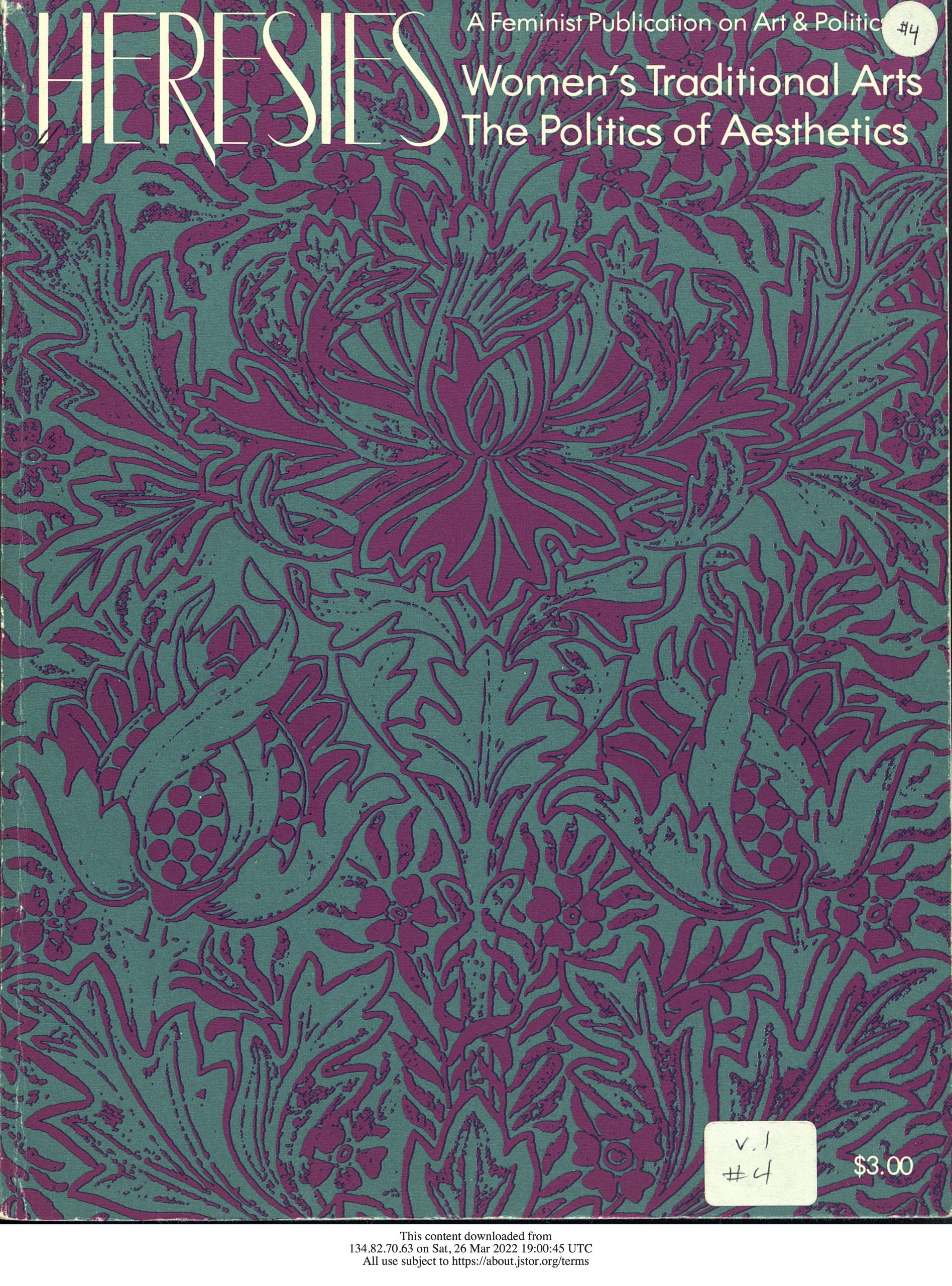

Anyone looking at her photograph and Self-Portrait (1948) can see that Kahlo was a striking beauty. With her full lips, pierc- ing black eyes and heavy connecting brows, she would have attracted attention any where. But she enhanced her exotic appear- ance by choosing as her daily attire the costume of the women from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—an embroidered blouse and a long skirt of purple or red velvet with a ruff- led hem. In many self-portraits, Kahlo wears an elaborate Tehuana headdress that drapes over her shoulders like a shawl and frames her face with pleats of starched lace reminiscent of an outsized Elizabethan ruff. Frida Kahlo arranged her hair in intricate Mexican hairdos decorated with ribbons, clips, combs and flowers. She adored jewelry, and her hands were a constantly changing exhibition of rings. In U.S. cities and in Paris, Frida Kahlo was a traffic stop- per and a hostess’s delight. Art dealer Julien Levy remembers the commotion Frida Kahlo once created in a Manhattan bank when she walked in followed by a pack of children crying, “Where is the circus?

Kahlo did not choose her picturesque clothing simply out of exhibitionism, though a taste for spectacle may well have been part of her motive. As her self-portraits in Tehuana costumes show, her reasons for dressing that way were complex. If one com- pares Frida Kahlo’s self-portraits as a Tehuana with the depictions of women in Mexican costumes by the nineteenth- century “Costumbrista painters, or even with Diego Rivera’s portrait of Frida as a Tehuana in a San Francisco mural, one de tects something intensely charged and peculiar in the relationship between Kahlo and her costume. In some paintings, her Tehuana dress hangs empty, without Frida in it. The costume seems to have little to do with local color and much to do with a dis- junctive sense of her own identity. Sur- rounded by the lace headdress, for example, her dark, slightly mustachioed face looks perverse and even demonic. Her features are determinedly composed and yet brim- ming with emotion.

On the simplest level, Frida Kahlo might have dressed in Tehuana costumes because she loved exotic objects that brought the aura of distant places to the confinement of her Mexico City home. Perhaps because she was an invalid and acutely aware of the fra- gility of her hold on life, Frida Kahlo had a strong love for material objects. She amassed a large collection of “little things"—dolls, toys of clay or straw, costumes, jewelry, pre-Columbian idols and all kinds of popular art. She relished the concreteness of these objects, 1 suspect, as well as their novelty or visual appeal. Kahlo’s friends recall the pleasure she took in the presents they brought her. Souvenirs of other people’s wanderings must have precipitated imaginary voyages in her mind. Two years after her bus accident, seventeen- year-old Frida wrote to a friend, “My greatest desire for a long time has been to travel. All that is left to me is the melancho- ly of those who have read travel books.

Most likely she was not consciously iden- tifying with any specific ethnic myth when she chose the Tehuana costume from the many regional costumes Mexico has to of- fer. (Kahlo did sometimes wear costumes from other areas of her country as well.) Tehuantepec women are famous for being stately, beautiful, smart, brave and strong; according to legend, theirs is a matriarchal society where women run the markets, han- dle fiscal matters and dominate the men. Al- though association with these characteristics would not have displeased Frida Kahlo—it probably would have amused her—her selection of the Tehuana costume simply be- cause it was pretty and festive would be more in character. In fact, she said she wore it out of coquetry: she wanted the long swaying skirts to conceal a limp caused by a bout with polio at the age of six that left one leg longer than the other; she also wanted the costume to hide her injured foot.

Besides disguising defects, wearing the Tehuana costume expressed a point of view. It was a statement of Kahlo’s passionate identification with her Mexican heritage, an identification stressed by Kahlo’s witty, but consciously vulgar, marketplace manner of speaking. Although her father was a Ger- man Jew of Austro-Hungarian descent and her mother a Mexican of mixed Spanish and Indian extraction, Frida Kahlo emphasized the Indian in her ancestry. The value Kahlo set on all things native and on all things made by what she called “la raza (the people) was shared by her husband Diego Rivera and by a whole generation of artists and intellectuals in post-revolutionary Mex- ico. Their fervent “Mexicanismo went hand in hand with the adoption of a certain primitivism of style and subject matter in the arts. The folkloric impulse in Mexican culture of this period can be taken as a gen- erally leftist, anticolonialist political state- ment. Nativism also led to an enthusiastic investigation of the popular arts—including regional costumes. When Anna Pavlova danced a Mexican ballet in Mexico City, she wore a native costume. It was not long before sophisticated urban women adopted the idea for everyday fashion. For example, the Riveras’ friend, the painter and photo- grapher, Rosa Rolando (born in Los Angeles) managed to look more Tehuana than the Tehuanas by braiding her hair and wearing Tehuana garb. Her husband Miguel Covarrubias, the writer, painter and cartoonist for Vanity Fair, helped to popularize this “Indian look when he wrote rhapsodically about the Tehuanas in Mexico South, published in 1946.

In the 1940s, the cult of Indianism spread to bohemian milieus in the United States. I suspect that both for Frida Kahlo and for urban women in other parts of the world, dressing in peasant costumes had to do with the notion that the peasant is more earth- bound and therefore more deeply sensual than the urban sophisticate. To dress in this exotic way, instead of wearing tailored city clothes, gave women a sense of abandon, a permission to feel uninhibited about their bodies. Men liked women to dress in peasant styles too, for in a sense this cloth- ing joined the idea of the earthy, sexual peasant to the idea of the female as nature, not culture. Thus by wearing Indian cos- tumes women declared their primitive con- nection with nature and their own sexuality. In addition, there is a political dimension to their identification with this popular art form. As usually happens when folk cos- tumes are adopted by sophisticated people, this peasant style did not catch on with men, in Mexico or in the United States. Diego Rivera, for example, chose to wear denim= worker’s overalls, not the familiar white shirt and pants of the Mexican Indian, to assert his espousal of antibourgeois values. Similarly, in some of her more specifically political moments, Frida Kahlo cropped her hair like a boy and wore denim skirts and work shirts decorated with the Communist star or the hammer and sickle.

Rivera loved the look of the Tehuanas and he brought back costumes for Frida from his trips to Tehuantepec. His enthus- iasm for Tehuanas is seen in a series of oil paintings of Tehuantepec women he painted in 1929, the year he married Frida. (Tehu- anas also appear in his murals and in a 1935 series of watercolors of Tehuantepec scenes.) Very possibly Frida Kahlo caught Diego s enthusiasm. Before she married, Kahlo dressed in European-style clothes. Her first self-portrait (1926) shows her as an elegantly dressed woman. But, what was unusual for those times, she occasionally wore pants, perhaps to cover the scars from her acci- dent. It was only after her marriage that Frida began to dress and to paint herself as a Tehuana, and it is likely that she did this to please her husband as well as to please herself. Perhaps significantly, Frida ex- plained that the Tehuana Frida in her dou- ble self-portait, The Two Fridas (1939), was the Frida Diego had loved, while the Frida in the white, European-style, Victorian dress was the Frida Diego had stopped lov- ing during the year they were divorced. The possibility that Frida Kahlo wore Tehuana costumes partly to please Diego is also sug- gested in Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), likewise painted during her divorce from Diego. Here she has cut off her long hair and dressed herself in a man’s suit large enough to have been Diego s. By destroying attributes of sexuality (the long hair and Te- huana clothes that gave pleasure to the man who had betrayed her), Frida has commit- ted a vengeful act that only serves to height- en her pain. (They remarried in 1940.) Frida became famous for looking like an Indian princess or a goddess. No doubt her eye-catching appearance delighted Diego, who revelled in publicity. He did not hesi- tate to make a political issue out of Fridas clothes, and once expounded to a Time magazine reporter:

The classic Mexican dress has been cre- ated by people for people. The Mexican women who do not wear it do not be- long to the people, but are mentally and emotionally dependent on a foreign class to which they wish to belong, i.e., the great American and French bur- eaucracy.1

Frida Kahlo, said Rivera, exaggerating as was his wont, had worn only Mexican clothes for 22 years. Nevertheless, he was thrilled with the effect of Frida’s appear- ance on bourgeois Paris; when she went to Paris in 1938 for an exhibition organized for her by André Breton, Schiaparelli designed a decidedly haute couture robe Madame Rivera.

By wearing the Tehuana costume, Frida Kahlo created an art object of her scarred and crippled body, and she helped to make herself a living myth. Perhaps the elaborate packaging was an attempt to compensate for her body s deficiencies and for her sense of fragmentation, dissolution and imminent death. A costume can make the wearer feel more visible, more emphatically present as a physical object in space. For a frail, ofter bedridden woman, this need to establish a theatrical physical presence to confirm her existence must have been strong. Surely this was one of the reasons why Kahlo painted herself so many times.

In addition, the flamboyant costumes. together with Frida’s allegria and aston- ishingly direct, earthy behavior, might have been antidotes to the pull of introversion. As her many self-portraits show, Frida Kahlo spent much of her time investigating and communing with herself. Her costumes might also have been distancing mechan- isms. They may have allowed Kahlo to dis- sociate herself somewhat from the painful aspects of her reality. And by wearing color- ful costumes Frida could distract friends’ at- tention from her physical suffering. In her self-portraits, tears always signal physical or mental pain, but Frida s features always are unflinching. Her self-portraits are charged with a strange tension because of the contra- dictions between her festive exterior and suffering interior. Perhaps Frida Kahlo hid behind the exquisite decorative object that she presented to the world. The Tehuana costumes were for her both mask and frame.

1. Fashion Notes, Time Magazine, May 3, 1938.

Hayden Herrera, an art critic, is currently working on a book about Frida Kahlo for Harper and Row. She is curator of a Frida Kahlo exhibition which opened at Chi- cago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in January 1978.